Hospitals often try to improve perioperative performance by fixing visible metrics, such as turnaround time and first case on-time starts. The effort feels productive, but results rarely change. Why? Because they might be addressing the wrong problem. The problem is not execution, but perspective. Perioperative services are a system, and optimizing individual metrics does not optimize the system.

It’s like a football team with a new star quarterback. He may have good wide receivers and innovative coaching. But if the offensive line can’t keep him upright and there is no running game, the talent goes to waste. Even flawless performance at one spot cannot overcome breakdowns elsewhere.

Turnaround time is a useful example. Hospitals routinely invest significant effort and expense to shave minutes between cases. New staffing models are introduced, roles are redefined and leaders monitor dashboards closely. Surgeons are happier and momentum feels apparent. But in many cases, throughput barely changes. Why? Because faster turnovers only matter if there is another case ready to go, a staffed room to receive it and a schedule designed to absorb the gain. When those conditions are absent, improved turnaround time merely creates idle space rather than additional capacity.

The same pattern appears with first case on-time starts. A punctual beginning helps, but it does little if schedules are fragmented or downstream constraints accumulate as the day unfolds.

Where capacity really goes missing

In one recent case, leaders assumed turnover time was the main constraint, and data suggested only modest gains were possible. A systemwide view told a different story. Over a year, thousands of OR hours were lost to schedule gaps driven by poor case sequencing, misaligned block time and inflexible physician schedules.

In other words, the largest opportunity was not inside the OR at all. It lived between processes.

This is a common finding. There are so many opportunities for capacity to vanish: in the handoffs between scheduling and staffing, between block design and physician behavior, between authorization workflows and day-of-surgery readiness.

These gaps are harder to see and harder to own because they often do not belong neatly to any single department. Most perioperative leaders operate within well-defined lanes. OR leadership focuses on room utilization and staffing; medical group leaders focus on physician access and productivity; revenue cycle teams focus on authorization and payment; and supply chain focuses on readiness and cost. Each group is doing its job.

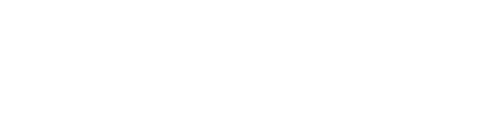

The problem is that the jobs are interdependent. When each function optimizes for its own objectives, the system as a whole becomes unstable. Improvements in one area shift pressure to another. Bottlenecks don’t disappear, they just move.

This is why perioperative improvement efforts can stall. If no single leader has visibility or authority across the entire ecosystem, no shared understanding of how decisions interact exists. Well-intentioned changes can create unintended consequences. Perioperative systems are dynamic: small changes can have cascading effects.

From gut feel to informed decisions

Solving this problem requires better decision-making capabilities, but traditional tools are poorly suited to this task. Spreadsheets and static reports can describe what happened yesterday but struggle to predict what will happen tomorrow.

Advanced analytics and scenario modeling offer a different approach. For instance, what happens if block length changes, or if staffing patterns shift, or if authorization timing improves, or if physician schedules are adjusted?

By modeling scenarios in advance, organizations can see trade-offs before making commitments. They can identify where improvements reinforce one another and where they conflict. Most importantly, they can focus effort where it will actually change outcomes.

When perioperative services are treated as a coordinated team, performance looks different. Schedules become more predictable, idle time is reduced without exhausting staff, physicians gain more reliable access without constant escalation. Leaders spend less time firefighting, and financial performance improves through better design.

Hospitals that make progress in this area do not abandon familiar metrics. Rather, they contextualize them. Turnaround time still matters, but only insofar as it supports throughput. On-time starts still matter, but only as part of a schedule that can flex with reality.

The shift is subtle but profound. The question changes from “How do we improve this metric?” to “How does this change affect the system?”

A more realistic path forward

Perioperative performance will never be simple. It is inherently complex work involving hundreds of moving parts, people, incentives, variability and competing priorities. There is no single fix and no universal benchmark that guarantees success. But there is a clear lesson from organizations that move the needle: sustainable improvement comes from seeing the whole field.

This means resisting the temptation to chase the most visible metric. It means acknowledging that many of the biggest opportunities live between departments. And it means investing in the tools and governance needed to understand how the pieces fit together.

Hospitals might not need a new star quarterback. They do need a playbook that suits the entire offense.

Why perioperative improvement projects often fail

- Single-metric fixes don’t work

- Capacity is lost between processes

- Siloed ownership creates instability

- Systems thinking matters more than local optimization