Payers and providers are increasingly creating strategic partnerships, with the intent of keeping pace in a rapidly transforming healthcare payment system that rewards value over volume—by managing costs, improving population health, and improving the customer experience. The models for potential partnerships run the gamut from contractual agreements for specific lines of business to joint ventures to the creation of new, fully integrated companies. For all partnerships, regardless of their specific form, balancing competing priorities is a critical—and continuous—task that will determine the shape and success of the partnership.

Payer-provider partnerships are intended to create economic value—by making healthcare more affordable, convenient, and personalized—that can be translated back to consumers, creating a virtuous feedback cycle. This value creation takes place as providers gain access to the health plan’s premium dollar, while payers gain access to the point of care. For the communities served by the partnership, the efforts are ultimately intended to reduce the overall cost of care.

Health system and health plan leaders must be prepared to guide nascent partnerships forward through uncharted terrain. Sustaining success requires organizations to identify and deftly navigate a series of critical economic tradeoffs, including the creation of value through the partnership relative to its size, the methods for measuring performance, and the assumption of risk. Key questions along this journey—whose answers will help chart the partnership’s economic parameters—include:

- Is our partnership big enough to create value that will realize its promise?

- Does our partnership measure its performance in a meaningful way?

- Does our partnership effectively balance potential risks and rewards?

Balancing Tradeoffs |

|

Image

Examples from both ends of the continuum for each trade-off are provided below.

Value CreationSmaller Scope Jointly owned health plan product focused on small employer group market where more than 90% of network providers are in the delivery system’s clinically integrated network. Due to the limited network scope, the scale of such a product is typically more limited (~10,000) relative to a more open access product.

Larger Scope Risk arrangement that encapsulates all members of the health plan that are loosely attributed to the delivery system and its clinically integrated network across commercial, Medicare, and Medicaid lines of business. Given the larger scope, the number of lives in these types of arrangements is often much larger (approximately 50,000-150,000 lives) depending on network scale. Performance Model & MeasurementLess Unique Partnership risk pool includes all lives in a single product, so performance is measured based on the margin (or loss) that the product generates.

More Unique Partnership risk pool includes a subset of lives from multiple products based on attribution methodology—with the attributed lives possessing a higher concurrent risk score. Therefore, true performance is more difficult to isolate, and any methodology may need to appropriately adjust for factors including population risk. Risk v. RewardLow Risk/Low Reward Can include economic models that do not incorporate downside risk for the provider partner and/or models that incorporate risk corridors that are so wide that there is no incentive to move away from status quo. High Risk/High Reward Can include economic models that make a multi-year commitment to an aggressive total cost of care target and view these targets as a forcing function for each party to do business differently. |

Big Enough to Matter: Creating Value

Payer-provider partnerships must ultimately cover a large enough share of the population and overall healthcare spending in the area it serves to effectively create value for the partnership—and reduce the total cost of care. For instance, a partnership caring for a population that accounts for a large portion of healthcare spending may have a relatively smaller cost reduction goal than a partnership responsible for a smaller portion of spending.

While reaching the size needed to create value may not be achievable in the near term, each party must be prepared to commit to growing the scope of the partnership, through steps that might include tying executive compensation to growth targets. As providers and payers shift from fee-for-service to value-based arrangements, the revenue generated by providers transforms into an expense. Participating providers will need to find ways to manage and reduce costs by reducing utilization, shifting utilization to lower cost settings, and potentially considering price discounts for commercial payers.

Without a sustained reduction of healthcare costs, health plans will not be able to offer competitive premium prices, which will in turn hinder efforts to maintain a resilient market presence. However, for the delivery system, growth—either through membership growth or greater access to the premium dollar—is a requirement to offset the expenses of the partnership.

Measuring Success

In order to quantify the creation of value through the partnership, and ensure that the return is commensurate with the investment, entities must accurately measure and isolate provider performance. Measuring the total cost of care within the partnership—and how it compares with national and market-specific averages—is paramount.

If the partnership’s risk pool is relatively unique in comparison to the payer’s broader risk pool, the need for more accurate measurement of performance around cost, quality, and patient retention will be heightened. However, overly complex approaches to measurement can distort the partnership’s ability to make progress toward its objectives; hinder efforts for providers to identify and respond to challenges; and even distort performance results, inhibiting the partnership’s ability to make progress.

Defining and Quantifying Risk |

|

As the amount of risk that the partnership is willing to take on grows, so does the potential for greater reward or loss. Ultimately, the partnership must be able to generate shared savings for both payers and providers, which is dependent on its ability to manage both the total cost of care for its members and overall administrative expenses.

As a starting point, partnerships should consider a series of questions to help define, quantify, and distinguish between different types of potential risk:

• How do we define risk as a partnership? • How do we adjust for risk? • How can we quantify much risk are we willing to take on? • How do we distinguish between clinical and performance risk, and actuarial risk related to pricing? • How do we distribute or delegate risk throughout our system? • How do we integrate the partnership’s risk into a broader risk management framework? |

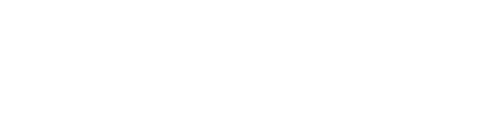

Payer / Provider Partnerships Range Based on Degree of Scope and Level of Vertical Integration |

|

Image

|

Balancing Risks and Rewards, and Pursuing Success

The amount of risk the partnership is willing to take on will ultimately determine the range of potential rewards or losses. Once partnerships define and quantify how much risk they are willing to assume, they must consider potential success factors and related opportunity costs.

For instance, to drive further growth, partnerships must be able to add new covered lives, either through membership growth or by assigning existing health plan members to the partnership. At the same time, partnerships must be able to keep overall patient spending within their network by closely managing cost and quality performance and effectively sharing information. A participating health system may work to realign its primary care network within the network to refer patients to the most efficient specialist, which may require data from their health plan partners.

The design of the health plans offered by the partnership also requires a careful balancing act. In many markets, there is a disconnect between payers and providers and the brokers who work directly with employers, regarding the type of plans that are offered or desired in the market. While employers may initially express an interest in low-cost coverage options, many employers eventually decide not to restrict choice in the plans they select, in order to maintain benefits that will attract high-quality employees.

Ultimately, partnerships must be able to translate the value they create back to employers, purchasers, and consumers—which is generally facilitated through the design of the health plans the partnership offers. While narrow networks that steer care to lower-cost care options can potentially help the partnership reach its overall goals, open access networks may be more popular with purchasers.

The growth and retention of the partnership’s covered lives also requires a balanced approach. Keeping consumers within the network and adding new lives is dependent on consistent results on quality and cost, which can lead to the introduction of out-clauses with providers based on performance metrics. However, the introduction of too many terms can also inhibit incentives for providers to create meaningful value in the care they deliver.

How Funds Flow Within a Partnership: From Current to Future State |

|

Image

|

Additional Considerations |

|

In addition to the key tradeoffs outlined above, payer-provider partnerships have multiple additional considerations to attend to over time. These include, but are not limited to:

• The degree to which both parties will maintain a pluralistic environment working with other partners in the market • The ability for participating entities to engage in multiple partnerships in their markets without diluting the value of a given partnership • The ways in which each partner will share in the economic performance of the partnership • Identifying the populations that the partnership will target—as well as their insurance coverage and the types of insurance products they are insured under • The ways in which the partnership can help each party begin the journey to a more collaborative, and less adversarial, relationship |

Success in a New Frontier

Payer-provider partnerships have the potential to improve the health of populations while reducing or controlling the overall cost of care. To achieve that vision, each partnership must be prepared to decide how to manage the creation of value, the measurements used to assess progress, and the amount and type of risk the partnership is prepared to take on.

While the particulars of each market will guide how partnerships determine their particular course of action, navigating economic tradeoffs and managing multiple considerations in the new frontier of payer-provider partnerships is critical for sustained success.

Kaufman Hall Senior Vice President Fernando Torres and Vice Presidents Max Timm and David Eagleton contributed to this article.