In early 2017, word was going around that Surgical Care Affiliates, Inc., was up for sale. According to its 2016 SEC filing, the company (since renamed SCA Health) operated 197 ambulatory surgical centers and seven surgical hospitals in 33 states, with approximately 3,000 affiliated physicians. In 2016, Surgical Care Affiliates had $1.3 billion in revenue—a 22% compounded annual growth rate since 2014—and $200 million EBITDA. Thirty percent of its shares were owned by private-equity firm TPG Capital.

If Surgical Care Affiliates was for sale, the question was, of course, who would buy it? An acquisition of this size would provide the purchaser with significant market share in a high-volume, profitable, and growing slice of the U.S. healthcare system. So, who would benefit from that market share?

By 2017, we were already about fifty years into a process of movement by for-profit companies into traditional not-for-profit healthcare services, with the pace accelerating significantly since the 1990s. The playbook of these for-profit companies was as clear as the objective was tempting. First, focus on slices of healthcare services that are high volume, high margin, high tech, least capital intensive, least dependent on government payers and currently not provided in a highly customer-friendly manner. Then, develop large, well-capitalized, tech-savvy companies to peel away those desirable slices of services from not-for-profit providers. Great for the new companies. Not so great for the legacy systems left with fewer, more complex, less profitable and, from a financial return standpoint, less desirable services.

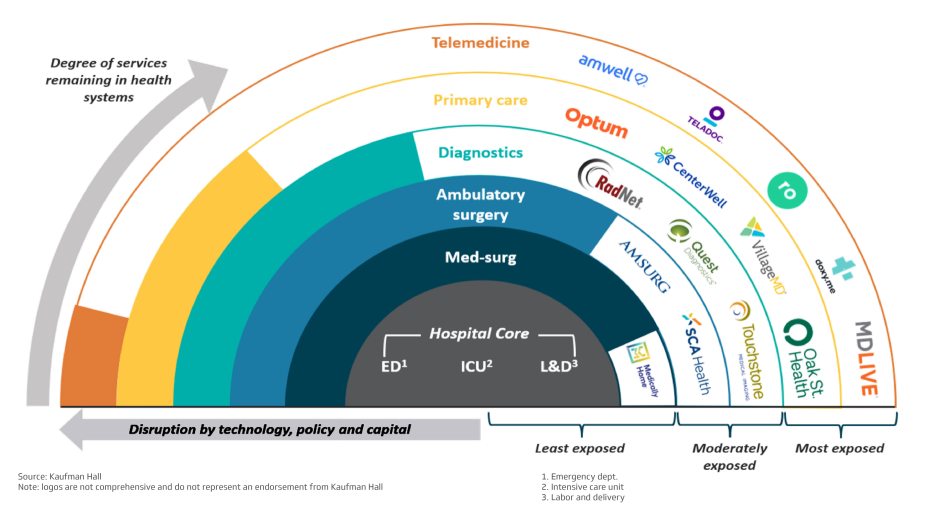

Figure 1 invites us to consider the competitive situation for services in the domain of U.S. not-for-profit health systems: medical-surgical services, ambulatory surgery, diagnostics and primary care, along with the burgeoning area of telehealth. The extent to which not-for-profits are vulnerable in each set of services is determined by the extent to which that service fits into the for-profit playbook. Areas of greatest exposure are telemedicine and primary care; areas of moderate exposure are diagnostics and ambulatory surgery; and areas of the least exposure, not surprisingly, are the highly complex, capital intensive, relatively low-margin inpatient medical-surgical services.

Figure 1 also shows the degree of advancement by selected for-profit companies in each of these categories of service. As the chart illustrates, corporate providers are not overtaking the provision of healthcare as a whole, but as time goes on, not-for-profit systems are getting a smaller and smaller portion of the total market.

Figure 1: Competition for healthcare services in key service categories

Not-for-profit health systems can respond in a number of ways.

One response is operational excellence: become as efficient as possible, controlling costs and optimizing revenue—difficult to do and hard to maintain. And such a response, by itself, does not always deliver strategic advantage.

Another possible response is scale: get bigger to more effectively compete with well-capitalized, for-profit disruptors—we have, indeed, seen major combinations creating larger health systems, although whether the scale achieved is sufficient to compete with for-profit encroachment, or has been used to that end, is an open question.

Another response is to partner with for-profit companies—something we have seen often, especially in digital and ambulatory services.

Yet another option is for not-for-profit systems to create their own focused, innovative companies—which larger systems have done, but mostly as an investment strategy, spinning off the new companies when they become desirable acquisition targets.

But could there be another strategy? Could large not-for-profit systems acquire for-profit healthcare service companies, thereby improving market position in segments of healthcare in which they are most exposed to disruption?

Rewind back to 2017. When Surgical Care Affiliates was available, aside from Kaiser Permanente, the largest not-for-profit systems ranged from $10 billion to $20 billion in annual revenue. Could a single not-for-profit system have afforded to purchase Surgical Care Affiliates? Perhaps, but none did. Or, could a group of not-for-profit systems have come together to purchase the company? Perhaps, but none did. At that time, and until recently, when such opportunities presented themselves, legacy not-for-profit systems, for whatever reason, tended to stick with their traditional ways.

Even if we did not know how the Surgical Care Affiliates story ended, most of us could have guessed: It was purchased by UnitedHealth Group’s Optum division for $2.3 billion, substantially bolstering UHG’s efforts to diversify from health insurance to healthcare delivery, a market presence UHG/Optum has continued to increase in the years that followed. And in 2018, Tenet Healthcare Corporation, another for-profit healthcare company, completed its purchase of United Surgical Partners International (USPI) from private-equity company Welsh, Carson, Anderson & Stowe, a process it had begun with acquisition of a majority stake in 2015. USPI today has more than 535 ASCs and surgical hospitals operating in 37 states.

Today, however, we appear to be poised for a change in the storyline.

In what almost feels like a repeat of 2017, on June 17 of this year, an announcement was made that another large, for-profit ambulatory surgery center company, AMSURG, had been acquired. AMSURG’s profile is strikingly like that of Surgical Care Affiliates at the time it was sold to Optum: more than 250 surgical centers in 34 states and more than 3,500 affiliated physicians. The reported purchase price was $3.9 billion.

The big difference is that this time, the buyer was not a for-profit healthcare company looking to build its presence in a profitable market segment, but a 175-year-old, not-for-profit, mission-driven health system: Ascension.

This purchase appears to signal that Ascension has decided to be a healthcare business as much as it is a hospital business. That’s a big statement about a system that includes 120 hospitals in 16 states, but is supported by the fact that AMSURG will increase Ascension’s number of ambulatory surgery centers a whopping six-fold. Before the acquisition, Ascension’s geographic footprint was primarily in the Midwest and South. With the AMSURG acquisition, Ascension will reach patients from Seattle to Miami and from San Diego to Boston. The acquisition of AMSURG does not diminish Ascension’s commitment to the hospital business, but it intensifies Ascension’s commitment to a different kind of business, a different kind of patient, and a different kind of geography. This strategic commitment should diversify Asension’s revenue stream, solidify its overall financial position, increase its impact on health of a larger portion of the country and extend its mission to meet the patients where they are.

These potential benefits come with risk. Running a national ambulatory chain that was born and bred in the private-equity, for-profit, corporate world requires a different mindset from that of a traditional not-for-profit hospital organization. However, the decision to make the AMSURG deal itself suggests that Ascension is already drawing insights from the corporate mindset.

Facing financial challenges coming out of COVID, Ascension has been doing the very hard work of rightsizing its portfolio—in the past 17 months divesting or consolidating about 35 hospitals. Most industry observers, myself included, found this to be a necessary and important effort. But following that effort up by making a strategic decision to change its entire healthcare ecosystem? That is a courageous strategic decision that I am not sure many saw coming.

Further evidence of a new mindset can be seen in how Ascension went about changing its ecosystem.

A system wanting to increase its role in a specific type of healthcare has a familiar decision to make about its strategy: grow organically, by building it yourself, or grow inorganically, through acquisition. The traditional not-for-profit mindset very much has favored an incremental, organic approach to growth. Corporate America, in stark contrast, favors a bigger, faster, acquisition-oriented approach to growth.

Ascension could have tried to grow its outpatient presence organically, but apparently decided that, although the system could have made some inroads using this strategy, the process would likely have been painfully slow. Instead, Ascension took the more corporate approach, opting for a far quicker path to material diversification.

What Ascension has done by spending almost $4 billion is to create for the system a new business model, and by doing so, create a new way of looking at what Ascension is and what it will be in the future. From my perspective, that is startling, in that we can find few previous examples of this sort of move from a not-for-profit healthcare organization.

Aside from being worthy of admiration, Ascension’s decision should prompt some important questions for other large, not-for-profit health systems. For example: How do we view the competitive outlook across the full range of healthcare services? What presence do we need in the various types of services to ensure our financial strength and strategic relevance? And, ultimately, looking at the different parts of the healthcare universe individually and collectively, how do we expect the game to be played moving forward, and how do we want to participate for the good of our organization and the people we serve?