After the pandemic generated large swings in payers’ key financial metrics—first, a tailwind of suppressed utilization that drove down medical loss ratios (MLRs) in 2020, followed by a headwind of resurgent demand that sharply cut per-enrollee margins in 2021—the health insurance market enjoyed a few years of relative stability.

However, even if industry-wide margins and MLRs are returning to their pre-pandemic levels, the world of payers and their target markets appears volatile once again. Declining profitability in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans has led some major payers to shrink their MA footprints for 2025, and CVS Health was even reportedly considering divesting its Aetna insurance unit, which would be a monumental shakeup if it came to pass.

Amid these changing conditions, payers operating health plans of all sizes may be left wondering what they can do now to ensure their organizational vitality and improve their relative market positions in the future.

In addition to internal efforts to become more effective and efficient across the organization, payers may want to consider inorganic growth strategies as an avenue to pursue the following benefits:

- Adding new capabilities suited to future needs

- Taking advantage of the window of opportunity opened by current market dynamics, especially challenges experienced by smaller plans that may now be willing to be part of a larger organization, as well as more reasonable valuations for digital health players

- Accessing new growth opportunities to diversify revenue streams

- Sharpening competitive edges by accelerating efforts to enter markets

- Taking advantage of the post-election environment of greater (though hardly complete) clarity on the incoming federal government’s strategic disposition towards various payer businesses and an expectedly greater openness to M&A

Defining the next phase of inorganic payer growth

The appeal of inorganic growth stems from the natural limits on what organizations, even the most successful and well-run, can accomplish through in-house efforts. However, as payers consider inorganic growth, we believe it is important to make clear and coherent choices on the strategic intent behind pursuit of inorganic growth. We find three main areas of strategic intent at play – scale, capabilities, and diversification, as payers aspire to get bigger, get better, and evolve to a different business portfolio respectively.

- Scale is probably the best understood of the three main strategic intents. By tapping into scale, payers unlock membership growth and access to new growth channels. Expanding your geographic footprint and increasing your number of covered lives can drive value by tapping into new markets, increasing the breadth of networks, and improving access to capital to invest in core operations. Scale initiatives can take multiple forms:

- Market scale grows membership in existing businesses within the existing geographic footprint.

- Product scale targets a specific product or line of business and extends the acquirer’s corporate and operational services to enhance the acquired product line’s performance and efficiencies. A “reverse integration” approach can also be taken by extending the smaller acquisition into a growth platform for the larger acquirer – United Healthcare’s acquisition of Surest (formerly known as Bind) could be considered an example here.

- Platform scale extends the existing technology and operational chassis to new kinds of membership while reducing administrative overhead per covered life.

- Capability acquisitions, including both operational enhancements to your organization’s platform and consumer experience improvements that offer competitive differentiation, can accelerate development along every layer of a health plan’s functional structure and make the entire organization more future-ready.

- Clinical and operational enhancements, which affect the base layers of functional structure, drive value by ensuring business continuity and financial sustainability, improving corporate efficiency, and enhancing an organization’s ability to scale in other ways. For example, one of our recent payer clients found their acquired company had a faster underwriting and quoting process and could learn and apply that to the entire organization.

- Consumer experience improvements, which impact go-to-market functions more directly, drive value by retaining or acquiring more members and enabling revenue diversification.

- Diversification efforts add new lines of business outside core product lines. These additional businesses drive value by managing risk among more tenuous lines of business, introducing cross-selling opportunities, and spurring future product development and expansion into more attractive growth and/or margin businesses. Potential diversification efforts could target:

- Operations and tech utilization—e.g. health benefit third-party administrators. Health Care Services Corporation’s (HCSC) of Trustmark is an example.

- Care delivery—e.g. physician groups or virtual care providers.

- Upstream integration—e.g. brokerages or member engagement companies. CVS Health’s acquisition of Hella Health, a brokerage, is an example.

Promises and pitfalls of inorganic growth strategies

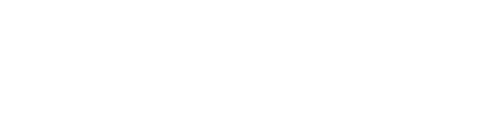

For every potential benefit offered by inorganic growth strategy, there will necessarily be a corresponding risk. Not only does this extend to specific capabilities and functional areas, but also to the organizations representing either side of a deal. Often, what advantages the sell side presents risks to the buy side and vice versa. Figure 1 below helps illustrate this dynamic while offering a scale-based argument for the value of inorganic growth strategies.

Figure 1: Distribution by Lives of US Health Plans, Profit Margin by Plan Size

This graphic makes immediately clear the challenges faced by health plans with insufficient scale. Most health plans with fewer than 1 million lives posted negative profit margins in 2023. As mentioned in the introduction to this article, this helps create a window of opportunity for pursuing inorganic growth. Thanks to factors such as risk pooling and administrative efficiencies, these smaller plans could expect their profit margins to improve if they either merged with other smaller and like-sized plans or were acquired by a larger plan.

However, given that around 30-40% of health plans with fewer than 1 million lives are still turning profits, and that over 10% of the largest plans are in still the red, affirms that raw scale alone does not, of course, determine profitability. Successful health plans looking to expand via the acquisition of a smaller, unprofitable plan must assess whether their target’s financial difficulties can be solved by joining a larger organization, or if factors such as their challenged market position would translate to dead weight even in a larger organization.

Conversely, for smaller but still profitable plans, the pursuit of scale via inorganic growth could amplify their success, such as by diversifying their risk pool, expanding into new markets, or gaining back-end efficiencies. However, they also run the risk of diminishing their organizational agility or degrading their member experience if they experience a difficult merger integration process. Figure 2 below further details how each benefit of inorganic growth comes with a corresponding risk that needs to be managed.

Figure 2: The Benefits and Risks of Inorganic Growth

Conclusion

Health plans interested in inorganic growth should reflect deeply to better understand their motivations as it relates to their strategic goals, assess their readiness for a deal in terms of risk tolerance and access to/need of capital, and define success by identifying specific target attributes and metrics for the lines of business, geographies, and/or capabilities selected for inorganic growth.

Rather than viewing inorganic growth as a hammer to a nail, where a lack of scale is the only problem a health plan might have and more scale to be its only solution, it is better thought of as a Swiss Army Knife, a creative toolkit that can serve any number of needs a health plan may have. We are in an exciting window of opportunity for health plans to explore how inorganic growth strategies can drive organizational vitality.

Kaufman Hall Senior Vice President James Tompkins and Assistant Vice President Callie Eberspeaker contributed to this article.

The authors would also like to thank Associate Rahul Tanna for his research and analytic support.