Aligning the right model and the right measurements with the right compensation

Over the past 25 years, health systems have significantly expanded their use of advanced practice providers (APPs) such as nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs). This isn’t news. But a closer look reveals something troubling: systems don’t benefit from them as much as they should.

Let’s start with what we know. APPs today represent an enormous portion of the U.S. clinical workforce. The primary reason: the U.S. physician shortage is serious, and APPs represent an affordable and available alternative. Physician shortages will remain a concern without expanded residency funding and medical school growth. APPs can dramatically alleviate physician shortfalls, particularly in underserved and rural areas.

Predictably, systems have grown to rely on them. APPs comprise 40% of the clinical workforce today, and given the landscape of financial challenges that health systems face, this figure is only projected to grow. By 2035, it is expected that APPs will play a central role in delivering every kind of care.

Yet despite this growth, many medical groups are seeing a troubling trend: a productivity lag, as measured in declining wRVUs per clinical full-time equivalent employee (cFTE). Simply put, systems that use more APPs often demonstrate lower per-clinician productivity.

APPs are often blamed for the decline in productivity. This is misguided. The problem isn’t with the APP; it’s with how the care team is organized. Reorganize the practice so that physicians and APPs both are working at the top of their scope, and a more profitable practice will result.

What’s causing the decline in the wRVU per cFTE?

Two factors drive the inefficiency. The first is accounting for the RVU or the encounter. In many organizations, physicians and APPs are credited and compensated for the same billable encounter. The second factor is a complex incentive structure in which physicians are paid on productivity, which the APP supports; but the cost of the APP’s employment lies with the health system.

The underlying issue is that practices often build care teams based on historic perceptions of the role of the APP or on the personal preference of a single physician. This frequently leads to inconsistent staffing, unclear roles and higher costs with no clear system-wide benefit.

If a practice’s profitability is declining year after year despite employing APPs, its leaders must ask tough questions. These might include:

- Why are team costs rising while clinician productivity is falling?

- Are physicians truly working at the top of their license? Are the APPs? How do we know? How do we shift to optimize the physician’s practice and that of the entire care team?

- Does our care model benefit physicians, patients and the system—or just one of the three?

- Do we measure performance differently for specialties or teams that rely heavily on APPs?

If the answers are uncomfortable, it’s time to rethink how teams are structured.

From individuals to a team: clarifying roles

The use of APPs is not new. But their deployment varies widely. In some systems, APPs independently manage patient care. In others, they are limited to inbox tasks, note-writing or order entry.

The cost may be similar, but the value decidedly is not. Only one approach meaningfully improves access and margin. When APP deployment is based on anything other than maximizing the practice’s productivity, inconsistent outcomes and inefficiency result.

Leading organizations now use a standardized framework crafted by role-based APP archetypes to clarify expectations and support effective deployment. These archetypes help answer core questions: How many APPs do we need? Does the APP work independently? What kind of clinical work should APPs do? How is productivity measured? How do we benchmark teams? How should their work factor into team productivity and compensation?

It must be said explicitly: there is no one-size-fits-all archetype. The best approach depends on multiple factors. But clarifying roles can help reduce variability, improve benchmarking and clarify situations in which subsidies are necessary.

Effective deployment, aligned incentives

With clarified roles, both physicians and APPs can be deployed at the top of their respective scope for maximized value. Consider the following example of two practices with identical interventional cardiology physician staffing but different APP deployment:

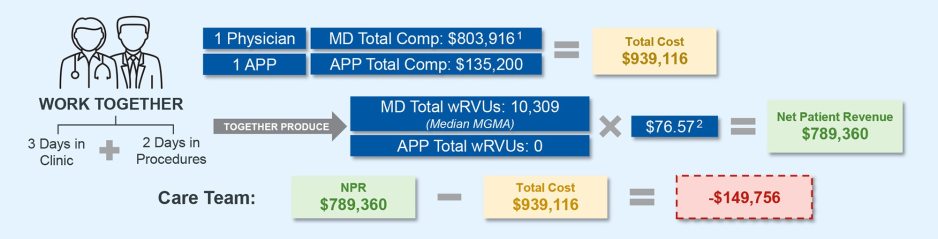

- In Figure 1, one physician and one APP work together. They generate 10,309 wRVUs but incur a $150,000 loss.

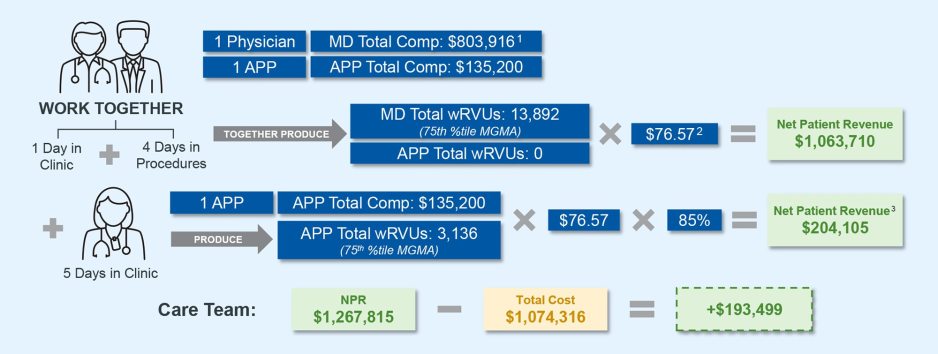

- In Figure 2, one physician and two APPs are strategically deployed—one for clinic, one for procedures. This frees up physician time to focus on higher-value work, increases wRVUs to nearly 15,000 and results in a $200,000 margin.

Figure 1: Inefficient Care Team Model

Figure 2: Efficient Care Team Model

The second practice obviously is the preferred model. It does not require new capital investment. It just demands a more thoughtful care team approach. Unfortunately, traditional compensation models don’t often support such an approach.

A physician performing at the 65th percentile in wRVUs (which is considered “high performing”) without APP support is far more productive than a physician at the same percentile working with two APPs. Yet, both may be paid the same.

This creates two problems: the organization overspends on labor for the same output, and it fails to reward the team effort that drives productivity. So, compensation models must also evolve. Options (and more than one may apply) include:

- Adjusting benchmark targets for physicians with supporting APPs

- Removing APP-generated work from individual productivity scores

- Benchmarking the whole team, not just the individual.

This ensures added resources lead to improved productivity.

Conclusion: Design care teams with intent

APPs provide an accessible option to close workforce gaps, improve access, support population health and enable physicians to operate at the top of their license. Most practices, unfortunately, don’t deploy them thoughtfully, leading to inefficiencies.

But the good news is, while falling productivity is unsustainable, it’s also reversible. When designed strategically, effective care teams increase access, boost productivity and improve margin. When poorly designed, they create redundancies, underuse talent and inflate costs.

To address this, organizations must shift away from measuring individual productivity alone and toward models that reward coordinated, team-based performance. Creating a model that drives both the physician and the APP to practice at the top of their scope is ideal.

APPs are essential to the future of healthcare delivery. But their value depends on how well they are integrated. To unlock their potential, organizations must define standardized role archetypes, prioritize team-based productivity and align compensation with collective objectives. This approach promotes access, sustainability and practice and system effectiveness. In short, it ensures the care team model drives value by design—not by chance.